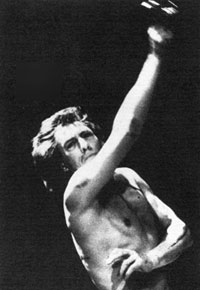

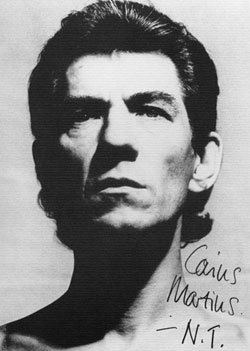

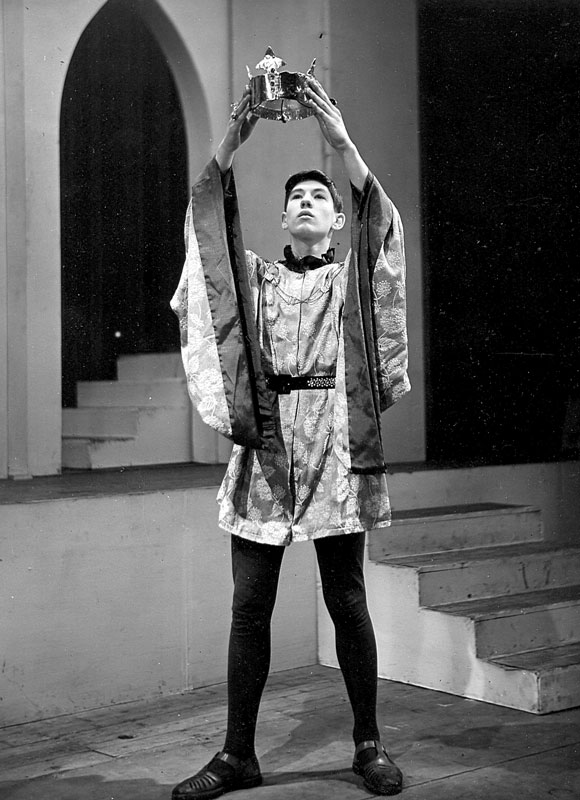

CORIOLANUS (1984)Theatre-life is full of crossroads (and cul-de-sacs, too): and if I hadn't left the RSC when I did, I mightn't have been free to play on Broadway in Amadeus, directed by Peter Hall. And if I hadn't done that, Sir Peter mightn't have invited me to play Coriolanus at the National Theatre.

As for my future with Shakespeare, there is no part I'm dying to act well, Benedick and lago, maybe, but only, as with any part, if the conditions (theatre, director, cast, pay) are propitious. There are (however,) parts that I'll try and avoid, because they somehow offend. Every modern, white actor, taking on Othello, feels obliged to explain why he's not playing him black, which was surely Shakespeare's intention, when the unspoken reason is that to 'black-up' is as disgusting these days as a 'nig- ger minstrel show'. Again, try as actors and directors may to explain what Shakespeare really intended, THE TAMING OF THE SHREW and THE MERCHANT OF VENICE stand, these days, as anti-feminist and anti-semitic. That crosses Petruchio and Shylock off my list. It's worrying, too, that RICHARD III seems to equate physical handicap with evil: which I don't. There are a few parts I'd like to have another crack at. I've still played Malvolio, only in that schoolboy letter-scene and I'm looking forward to Shallow again, in the hope that I may have forgotten John Barton's intonations. I keep Richard II and Macbeth fresh in my memory in ACTING SHAKESPEARE. Looking back at the rest, I've no regrets, even about the bad performances, because I learnt something from them all. No regrets, either, about missing out on parts that I'm now too old to play. Indeed, I'm ecstatic not to have had to try Bassanio, Ferdinand, Fliorizel and others of that ilk. Like Claudio and Sebastian they should be attempted only by charismatic beauties. It would have been fun, on the other hand, to play Edmund, Hotspur, Mercutio and Puck but, then, they are such easy parts - you never see a bad one. For me, over the years, acting in Shakespeare has always been a challenge. Accepting the challenge has always been part of the reward.

|

| First published as a souvenir booklet for the 31 August 1986 performance benefiting the Terrence Higgins Trust (Action Against AIDS) and the National Theatre Studio. |

| Ian McKellen's Home Page |