by William Shakespeare

Words from

Ian McKellen

Richard Cottrell, perhaps more than anyone else, was responsible for my

becoming a professional actor. After a couple of good reviews for an

undergraduate production of Shakespeare’s Henry 4th part 2 (with me as

Justice Shallow), Richard said “I suppose this means you will be getting an

agent soon” — a move that I had not contemplated before, although friends at

Cambridge, like Richard, already had their sights set on show business.

Six years later, as a director of the touring Prospect Theatre, Cottrell

invited me to play King Richard 2 for a five week tour of English regional

theatres. I was somewhat daunted, having acted in only two Shakespeares in my

five years since university, but this offer was a trusting confirmation that my

career was going well and, with Richard’s friendly guidance, I thought I might be

up to the challenge. We arranged for him to come over in the summer of 1968 to

plan the production in Ireland, where I was filming

Alfred the Great. How grown-up

this felt.

|

Richard 2

|

Richard 2 Richard 2

|

I had pored over the text a couple of times before his arrival in

County Galway and had been struck by two things: that Richard 2 is a family saga –

cousins, uncles, aunts, spouses – and that Richard’s initial belief in his own

invulnerability (a god on earth) separates him out from his relatives and his

courtiers so that his growing self-awareness turns him toward the frailty of the

common human condition. Over the kitchen table in a converted railway station

above a carpet factory, Cottrell concurred and allowed me to make a number of

staging suggestions.

Prospect Theatre was an impecunious outfit – low salaries, simple settings –

but had a formidable reputation for no nonsense, clearly-spoken productions of

classical plays. It was founded in 1961 by Elizabeth Sweeting (manager of the

Oxford Playhouse) and by Iain Mackintosh, who was later successful as renovator

and designer of theatre interiors. By the time I joined them, Toby Robertson

(another Cambridge graduate) was in charge. Had I not also been to Cambridge, it

is most unlikely that I should have been thought reliable enough by Robertson

and Cottrell to play such a leading role in their Company.

|

|

It was a great relief to feel the support of fellow actors during rehearsals

who deferred to my opinions in a way I hadn’t experienced before. Perhaps they

saw I was facing a massive challenge and didn’t want to get in the way. Perhaps Richard and I were just very clear about our joint intentions. I was

soon feeling a self-confidence which I hadn’t known before. In performance, I

suspect on reflection, that I may have been a little over-bearing to the

rest of the cast! I certainly recall whispering to minor lords to “get a move

on” in what Gwen Ffrangcon Davies once called “the pause while I’m not speaking”.

|

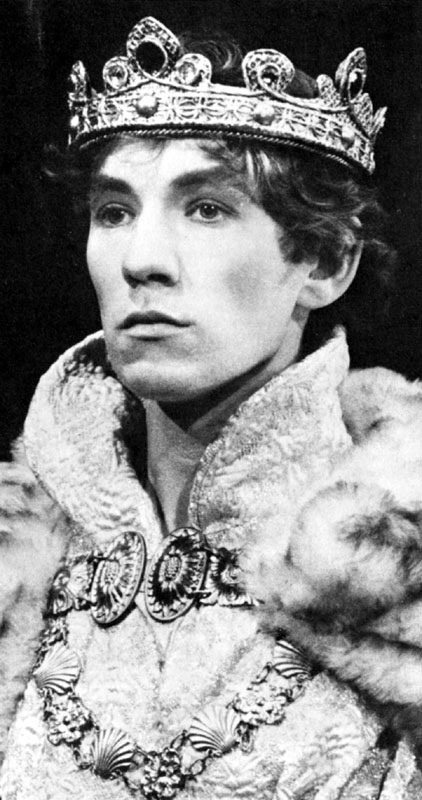

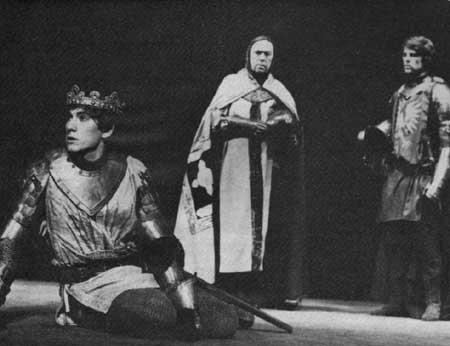

“How some have been deposed, some slain in war...” (III.2.157)

Richard 2 with his faithful supporters Bishop of Carlisle & Earl of Salisbury.

|

Richard 2 (III.2)

|

Richard has a lot to say for himself, and the language of early Shakespeare is

easy to speak – the rhythms of the blank verse are regular and the vocabulary

simple. Its formality is well-suited to the ceremonial structure of much of the

action. My experience under George Rylands for the Marlowe Society at Cambridge

was paying off. No one had to teach me about end-stops and iambic pentameters.

My major support onstage was from the icily calm Neil Stacy as Bolingbroke and

the ex-Stratford veteran Paul Hardwick booming and weeping as his father. In

Brighton, in the pub next door to the Theatre Royal’s stagedoor, we celebrated

Paul’s 50th birthday. I thought, aged 29, how amazing to still be acting at his

age.

"Therefore we banish you our territories." (I.3.139)

Paul Hardwick (Gaunt), Ian McKellen (Richard 2), Andrew

Crawford (Bishop), Stephen Greif (Mowbray), Robert Eddison (York)

Photo by: John Gilbert

|

|

There was a flight of moveable stairs on the set and little else, so Tim

Goodchild could spend the bulk of his meagre budget on the costumes. There was

plenty of room for regal processing and marching and as Richard’s decline set

in, for kneeling and crawling. By his last scene in prison, Richard padded along

the sides of a square like a polar bear I’d seen at London zoo, lunatic with

boredom and constriction. Richard is now more man than god/king and, as history

reports, I tackled my murderers with manly vigour.

How, before that, to play a man who knows he is divine? It is, of course, up to

the other actors to help in the way they bow scrape and behave in the presence

of holiness. I discovered that holding both hands up in blessing as I slowly

entered for the first time in gold and glitter established an aura of

invincibility. A Cambridge friend, Gabor Cossa (an ex-dancer) suggested I glide

rather than stride under my bejewelled gown. I recalled the way drag supremacist

Danny La Rue flounced about in his frocks and I borrowed his roller-skating gait.

|

Timothy Goodchild’s costume design for Richard 2’s heavy ceremonial gown, glittered with gold paint, golden thread and some metallic milk-bottle tops.

"We were not born to sue, but to command" (I.2.196)

|

Piccadilly Circus, 1970

|

But appearance and presentation aren’t enough and I needed to really

believe that an audience in 1968 could accept Richard’s “divinity,” and

therefore what makes the title of Tragedy credible – his acceptance of his own

humanity at just the point when his murderers arrive. Then I thought of the

Dalai Lama, who was accepted in Tibet as a divine incarnation, yet not by the

invading forces from China, which led to his exile. Wasn’t he perhaps a modern

Richard, without the tragedy, let’s hope? Anyway, I took encouragement that

there was in the 20th century a living god who was also a suffering man. So the

play was lifted out of mediaeval into our own times. This was not, however, a

modern dress production. I found further confirmation that Richard’s fate had a

modern relevance — in Hollywood, a city littered with the corpses of stars who

were treated as superhuman and could not cope with the strain. Marilyn Monroe,

perhaps, or Elvis Presley who was, of course, known as “The King”.

So I played Richard as a star, out of touch with reality and desperate

eventually for friends whom he had not had when the play starts.

Cottrell’s production was speedy and well-organised around the leading

role. The story was clear and our audiences responded well.

Ian

McKellen, London, May 2003

|